Tackling the Mundane

Having a job that requires staying on top of consumer trends has its benefits. Suddenly, some of my personal interests and pastimes…

Having a job that requires staying on top of consumer trends has its benefits. Suddenly, some of my personal interests and pastimes, rather than being a distraction from work, are actual assets. On top of that, as a 27-year-old female consumer, I might have insights into sectors that are less visible to others.

That said, I’m also wary of my ‘digitally-native’ lens on life. The segments that are most visible are probably the ones where a lot of the hard work has already been done. For the most part, they’ve already been ‘eaten by software’, and produced a bunch of hit consumer companies (repeat after me: past performance is not an indicator of future outcomes). Areas such as ecommerce, entertainment, media, social networks, on-demand platforms.

However, there’s a number of large consumer categories that fly under the radar, despite representing massive industries and significant proportions of consumer spending. Things like utilities, transport, and housing. Note: I’ve deliberately omitted healthcare, as, on an individual household/consumer level, the high household expenditure in the US is the exception, rather than the rule.

Seen from the outside, these industries look static. Mundane, even. Unyielding to change even as the internet and software reconfigure other areas. We know something isn’t working as well as it should, there’s little love for the status quo, but a new consumer playbook feels difficult to establish or difficult to even imagine. Sure, these days you’re able to compare prices online, the incumbents might have even launched an app, but the underlying incentive structures remain the same.

There’s a bunch of reasons that exacerbate this inertia, including a high level of regulation, concentrated set of incumbents, history of policy decisions that benefit incumbents, or fragmented supply where the product/service requires a high degree of trust and human interaction.

Achieving significant change in these categories requires more than just taking an existing, primarily offline product and putting it online. It’s necessary to take a first principles approach in order to build companies whose incentive structures are more aligned with those of the end consumer. That’s quite a bit harder to pull off than simply digitalising an existing product. This

Here are a few examples of companies working along those lines:

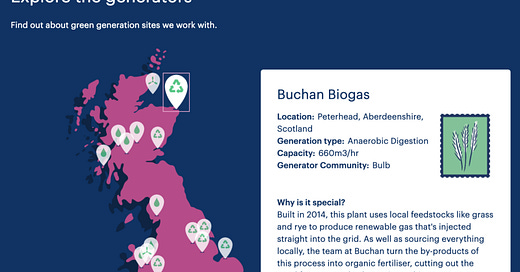

Bulb (utilities): Challenger energy provider in the UK that offers household gas and electricity, all from renewable sources. I’ve never heard someone speak enthusiastically about their energy provider until a friend described switching over to Bulb. Aside from providing affordable, green energy plans, they make it easy to join, explain where their energy comes from, and run a customer-focused service, already putting them miles ahead of the ‘Big Six’ energy companies in the UK.

Map of Bulb generators (bulb.co.uk)

Koru Kids (childcare): Managed marketplace for flexible childcare. Koru Kids connects nannies with local families who need part-time childcare. More families include working parents, increasing the demand for childcare, and current options usually involve after-school clubs or full-time nannies, a luxury few families can afford. Koru Kid’s staff are either students or older members of a community who want the flexibility of a part-time job. They deal with all the training and admin, whilst typically charging less per hour than typical nanny agencies.

Lambda School (education): Coding school with no up-front fees. This is a great example of the power of realigning incentives. University fees, notably in the US and the UK, have dramatically increased. Graduates are left saddled with student loans they have little hope of paying off in a reasonable timeframe, if ever (in the US, student loan delinquency rates are above 10%, higher than all other types of household debt). On top of that, a lack of focus and funding for vocational training/career paths has led to generations believing that the only road to success runs through university. Lambda School takes a different approach by offering software engineering courses without demanding an up-front fee. Students can either pay a lump sum at the start or choose to pay back a percentage of their income after they’ve landed a job above a certain salary, capped at a pre-agreed amount. Getting their graduates hired is baked into the Lambda business model, something that simply isn’t true for most traditional universities.

Lambda School students stats (lambdaschool.com)

Lemonade (insurance): Home and contents insurance. There’s very little love in the world for insurance companies, and for the most part, rightly so. Pricing isn't transparent, and most large insurance companies don’t foster a strong relationship with their customers, despite basing their premium calculations on the details of their lives. Lemonade provides a radically transparent option in a sector that hasn’t really moved much in years. They offer cheaper, easy-to-understand plans, explain how their business works, and as a certified B-Corp, support social impact causes with their profits.

Opendoor (real estate): Service that will buy your house, right now. Owing a house sounds pretty nice (I haven’t had the pleasure yet). Selling a house, however, is apparently still as annoying and time-consuming as it was decades ago. Yes, there are now online real estate portals, but the process of selling still involves listings, viewing appointments, and lots of negotiating. Opendoor lets consumers skip most of that by offering a competitive cash offer for a property and closing a sale within days. The former owner can move on with their life and Opendoor deals with selling the property. They’re able to pull this off by basing their prices on data about the property, similar properties in the area and regional trends. The fact that they have now dealt with thousands of properties across the US means that Opendoor probably has some of the best data and pricing mechanisms vs. the various regional, less data-driven incumbents.

The above companies operate in very different industries, but share a feature: Their incentive structures are more aligned with the end consumer than the incumbents. It’s what lets these companies create a level of customer love that was previously impossible in the category.

There are definitely more (but not nearly enough!) examples of companies that go beyond just digitalising, and rethink value chains to benefit the consumer. I’m looking forward to spending more time on ‘mundane’ sectors, and the founders trying to innovate within them. There might be fewer, but they‘re probably that bit braver.