The Pandemic and the Passion Economy

How Covid-19 is accelerating a new shift in how we think about jobs and livelihoods

What would you do if you got laid off tomorrow? It’s a question that I’ve heard debated more often in the last three months than in the seven years since I left university, combined. Perhaps an unsurprising consequence of witnessing a global pandemic that has shut down economies across the world.

In the UK alone, the latest data shows that 9.6m people — more than a quarter of the work force — are currently furloughed. So while they’re not working, they haven’t been fired either. They exist in a limbo where the government is paying the majority of their salary, while their employer tries to survive the crisis.

My friends and I have debated how ‘pandemic proof’ our own jobs are. We threw around ideas of how we would stay afloat and I was struck by how much broader the field of choices felt (granted, my living room would need a lot of work before it’s ready to become a yoga studio). But I was interested in what counted as ‘work’, or at least a viable income stream, compared to when I graduated in 2013.

Shifts in work & entrepreneurship

For a lot of working adults today, this isn’t their first rodeo with a major economic crisis. Each downturn has its own flavour, bringing with it challenges that result in different shifts in the labour market.

Where the financial crisis of 2008 spurred the growth of the gig economy, the current pandemic may fuel a new type of economic lever: The Passion Economy.

The passion economy, or creator economy as it’s also known, has been defined in a number of ways. It represents a new ecosystem that allows individual creators to monetise their skills. Li Jin, who writes extensively on the topic, talks about platforms where “Users can now build audiences at scale and turn their passions into livelihoods, whether that’s playing video games or producing video content.”

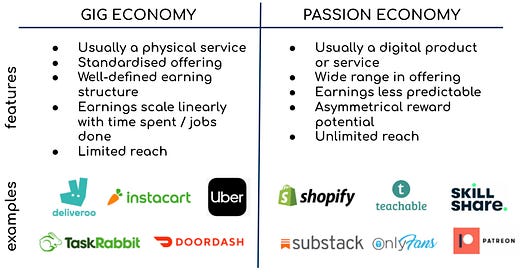

There are clearly overlaps with the gig economy. Platforms like Uber, Deliveroo and Doordash opened up new economic opportunities to millions. However many of the features that made these platforms thrive are also what restrict the level of success their participants can achieve.

Services provided in the gig economy are typically physical (e.g. ridesharing, deliveries) and commoditised in nature. A lot of the value comes from the ability to provide a standardised service. Participants have little agency besides controlling how many hours they work on the platform. This is also their main lever to increase earnings, which scale linearly with the amount of time they put in. So while your average Uber driver might be able to earn a decent amount from being on the platform, there’s a ceiling on how much they can make on any given day.

In the passion economy, many of these these restrictions are lifted. Creators have much more freedom and agency with the product they create. Having a differentiated offering is an advantage and the success of the creator and platform are more closely connected.

But perhaps the starkest difference is the potential upside for an individual creator. The amount of money they can make is not directly linked to the amount of time they spend on the platform. By producing a digital product or services that is distributed online, creators have access to a global customer base and can monetise around the clock.

So your yoga teacher (I re-committed to the practice during lockdown, can you tell?) that normally gets paid per class at a gym could record a lesson from home (or anywhere) instead. That lesson could be shared online, to an unlimited number of participants, all paying an individual fee to access that class. The students are likely paying less than they would for a ‘normal’ class, and the instructor makes more from that hour of content than they ever could in person.

Throughout lockdown there have been many examples of individuals who have joined the passion economy, either through choice or necessity. Workers that were furloughed or made unemployed have become online tutors. Wedding cake makers who have seen their bookings evaporate this year are teaching patisserie techniques online. Fitness instructors that can no longer serve clients in gyms are live streaming workouts from their own homes.

Some are using existing social media apps to deliver their services or are joining new platforms that cater to their specific sector. In her latest blog post, Li Jin talks about the opportunity emerging from vertical-specific platforms and the ways they can broaden the market for new types of work.

No silver bullet

The passion economy doesn’t come without its own challenges. The upside may be much higher, but being successful in this ecosystem is arguably harder than in the gig economy. Whilst the gig economy is more restrictive in terms of services, it provides a well-defined framework for what’s expected from the participants. In the passion economy, the onus is entirely on the creator to produce something that people want access to. Platforms may offer support in building up content and an audience. But they’re not aggregating demand in the same way that well-established gig economy platforms do today. Not everyone who might thrive in the creator economy will have the spare time, energy or resources to build up a following or portfolio of content.

The passion economy is not suddenly going to be the silver bullet for the problems in the labour market. The gig economy will also continue to be an important part of the ‘jobs stack’. But as we enter a new period of economic uncertainty, one of the few silver linings is the acceleration of this relatively nascent ecosystem. Just last week it was reported that Substack, the publishing platform, has more than 100,000 paying subscribers, saw its usage double and revenue increase by 60%, all within the first three months of the pandemic.

Polina Marinova Pompliano, founder of The Profile (which is published on Substack), left her day job at Fortune to start working on it full-time in the middle of the pandemic. Some might see this as an incredibly risky move, but she’s remarked on how her income has become more diversified since going independent, given her a type of security she wouldn’t have achieved as a full-time employee.

“I’d argue that people who think they’re in a “safe” job at a large corporation are in a far more dangerous situation than an entrepreneur starting from scratch. That’s because the second your company lays you off, your entire revenue stream evaporates.”

Making money on the internet is nothing new, but the growth of creator-centric platforms may give more people the opportunity to generate new revenues, fill income gaps and diversify their livelihoods. I’m excited about the potential for people to achieve that with more freedom and authenticity than was possible with previous systems.

If you have any thoughts on the topic or are building in this space, please comment or get in touch.

Further reading:

Unbundling Work from Employment - Li Jin

Shopify and The Key Decision for Business-in-a-Box Platforms - Nikhil Basu Trivedi

Great post. We r rediscovering ourselves, how to overcome adversities.